You Can See Where This is Going

The most fascinating part of history is trying to understand how people exactly like us could behave in ways we cannot fathom.

Take an example from Harvard psychologist Steven Pinker’s book The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined

A treatise on how people become less violent over time, the book explains barbarous practices that used to be normal. One was animal torture, a fixture of public entertainment for most of history until the 19th century. The details of what took place don’t matter. What matters is that the majority of society found animal torture perfectly acceptable for most of history.

“Spectators enjoyed cruelty, even when it served no purpose,” Pinker wrote. “Torturing animals was good clean fun.” Crowds — which included the noblest of kings, queens, and priests — “shrieked with laughter as the animals” were killed.

The common reaction is to consider these people monsters. But they weren’t. Biologically, they were no different from you or me. And the crowds who enjoyed these events were so large and diverse — so representative of the entire town — that we can’t chalk this up to a few sadistic freaks. Violence and torture 300 years ago were as socially accepted as, say, contact sports are today. How can this be?

It’s a complicated topic, but here’s a simple idea that helps explain how cultures settle on norms: Life was abjectly miserable for almost everyone 300 years ago.

And misery in your own life limits how much mental bandwidth you have for sympathy toward others. Animal welfare barely registered as relevant when the health of your own children was so tenuous, and famine and plague lurked around every corner. Life was a daily battle to protect yourself.

As generations rolled on and life improved for nearly everyone, norms changed. Better health, more comfortable living conditions, and more prosperous jobs meant less time worrying about your immediate surroundings, which opened the doors up to empathizing with how others were doing.

Life has improved so much over the last 300 years that we now have enough bandwidth to consider the wellbeing of not only other people but also animals. This is how all progress is made.

Sometimes progress is slow, but the overall trend has been intact for hundreds of years. Most generations enjoy higher living standards than their parents, which makes their lives a little easier, which opens the door a little wider to empathy and understanding. Which means every new generation has a little less tolerance for violence, mischief, dishonesty, and oppression.

This is obvious when looking at how attitudes toward violence have shifted over the last 300 years. It’s less obvious in shorter periods, like thinking about how millennials view the world differently from their parents.

Today’s younger generation does view the world through a different lens than their parents. Information barriers that slowed their parents down are gone. Data that used to be buried is now open. Social connections that used to be out of reach are now instantaneous.

You may not think millennials’ lives are easier. But they are more connected and informationally efficient than any other generation. The information age has opened their eyes, at warp speed, to how other people live. Just like dozens of generations before them, this pushes their view of the world a little closer toward empathy and understanding other people’s plight.

And their view is increasingly important. Millennials are in the process of two big trends:

-

They are moving into top management and political positions.

-

They will inherit $30 trillion from their baby-boomer parents over the next 30 years.

Most financial forecasts attempt to calculate how much stuff people will buy. This report does something different. It views business and investing in the coming decades through the lens of a generation that has a little less tolerance for deception, dishonestly, exploitation, and opaqueness than any that came before it.

It promotes one idea: The generational transfer of wealth and power to millennials shifts the center of gravity toward a world where two things — transparency and companies taking care of all stakeholders — become an important part of every investment thesis.

The idea of socially responsible business and investing is often interpreted as a soft, impractical ideology in a world driven by profit. “Hippies trying to take over Wall Street,” a friend put it.

This report will argue otherwise.

Moving toward social good doesn’t come at the expense of investment returns; rather, the move can actually bolster them.

To understand where we’re going, we first have to go back 114 years and remember how we got here.

Part 1: Transparency

Information has been scarce for most of history. Audited annual reports weren’t the norm until Depression-era regulations forced stronger disclosure. Food companies weren’t required to be “honestly labeled” until the Supreme Court forced them to in 1965. The Federal Reserve didn’t tell the public what it was doing with interest rates until 1994 — investors and economists had to reverse engineer what it was doing.

This is changing, fast. And it’s one of the most significant changes of the last 50 years.

A big difference between today’s young generation and those before them is the expectation that all pertinent information not only be disclosed and verified but also easily accessible. They have this expectation because the biggest progress the economy has made in the last 30 years is exposing information that used to be buried, either because it was too hard to make public or served someone’s interest to keep it out of sight.

We’ve gone from an age where investors didn’t know how much profit a company earned to being able to look up a company’s employees on LinkedIn to see where they went to college. This is not a small shift.

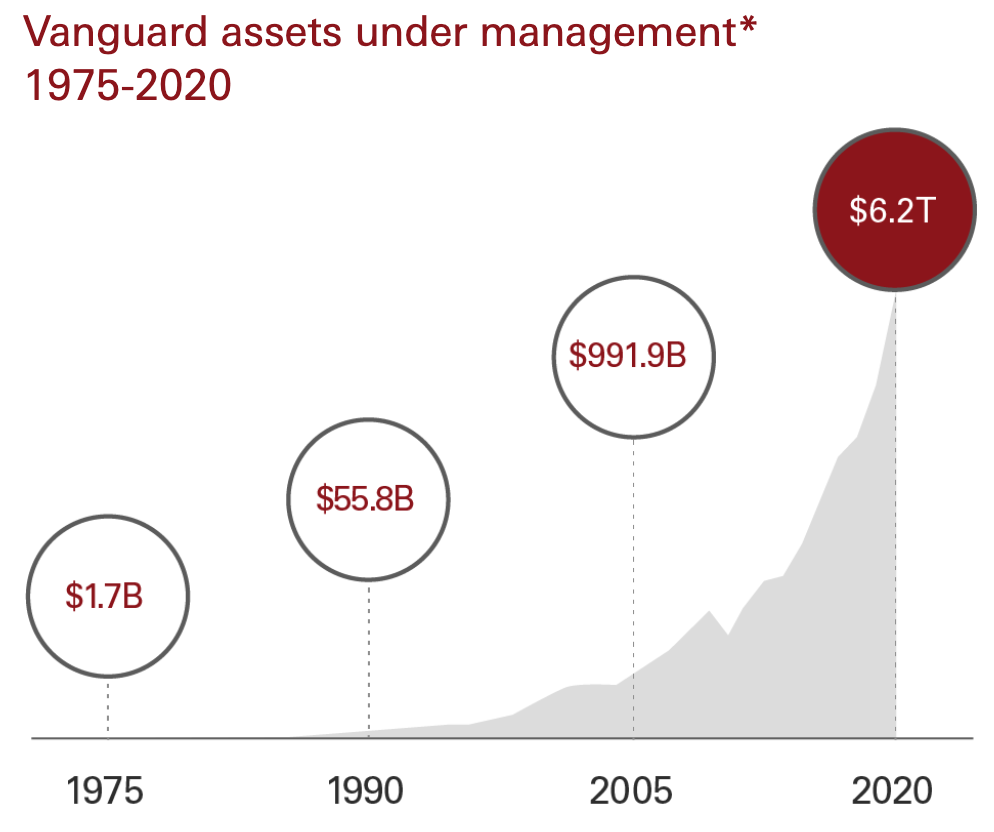

To understand how much impact the new age of disclosure and transparency has, consider the rise of the Vanguard Group.

John Bogle started Vanguard in 1974. His idea was not theoretical. It was basic arithmetic: The net return stock investors pocket is whatever the market generates minus all costs. So, on average, investors with the lowest costs will pocket higher returns.

It was so easy, so inarguable, you’d think it would catch on quickly. But it didn’t.

Vanguard effectively went nowhere for two decades after launching, despite offering the lowest-cost investment products around that consistently outperformed its high-cost rivals.

As early as 1991, Fortune magazine recognized that Vanguard investors “start each year more than a full percentage point ahead of the competition” thanks to its low-cost structure. Yet it managed just over $3 billion — a tiny sliver of the fund market, even back then.

Why did Vanguard have trouble getting people’s attention? My dad purchased his first mutual fund in 1991, so let’s consider his experience. He needed information to make his decision on what fund to buy. Yet:

-

There was no Morningstar.com

-

There was no Yahoo Finance

-

There was no Google Finance

-

There were no financial-advisor blogs

-

There was no Twitter

So he did what everyone did in 1991. He went to his local stockbroker who recommended a list of mutual funds — none of which were Vanguard funds, since Vanguard funds didn’t charge high enough fees to pay the broker a commission.That was their whole advantage in the first place. But since information was expensive back then — its price tag was the broker’s salary and bonus — Vanguard didn’t go far.

That changed in the mid- and late 1990s. Vanguard’s assets jumped from $55.8 billion in 1990 to $992 billion by 2005, to more than $6 trillion today.

What changed over the last 20 years wasn’t Bogle’s arithmetic. It was access to information.

People like my dad, who before the mid-1990s relied on salesmen for information, could suddenly look it up themselves. They could easily compare products based on information that was suddenly accessible and nearly free. With this new access to information, Bogle’s arithmetic sold itself.

As Jason Zweig of The Wall Street Journal put it: “As Hemingway wrote, bankruptcy happens ‘gradually and then suddenly.’ The popularity of indexing occurred the same way.” On the other end, high-cost managers have experienced more than half a trillion of redemptions in the last decade.

Vanguard is a clear example of something important: When information is expensive, as it was in my parents’ generation, you could get away with keeping the truth away from your customers. You could hide. That’s no longer the case. Whether it’s Morningstar, Yelp, Glassdoor, or Amazon reviews, customers’ ability to compare your product to the competition is now nearly perfect.

And it means businesses that hope to succeed over the coming decades will only do so by adding honest, transparent, and comparatively superior value.

It’s happening all over the place. Financial advisors are switching from commission to flat fees, which put customers’ interests first. Consumer companies are highlighting where, how, and by whom their products are manufactured. Everlane, a clothing company, breaks down how it settled on the retail price of its clothes, showing how much of your purchase price goes toward supply, labor, shipping, and profit.

For most of history, customers’ impression of a company was shaped entirely by what the company wanted people to see, which it controlled with marketing. Now customers can see what the company would prefer stay hidden. This age of transparency — which the young generation demands — forces viable companies toward honesty and integrity.

This is not to say that bad behavior doesn’t exist. It always will. But there are fewer places to hide for companies that don’t add legitimate value for their customers.

Jeff Bezos once said:

The balance of power is shifting toward consumers and away from companies. The right way to respond to this if you are a company is to put the vast majority of your energy, attention, and dollars into building a great product or service and put a smaller amount into shouting about it, marketing it.

Michael Dell said something similar:

You can’t trick the consumer anymore. The businesses that had an advantage because they sold things in a geographic area where people had limited information, and they couldn’t travel to go buy something else — those folks are in real trouble. The [Internet] kind of destroys that business model.

There have always been three (legal) ways to run a business:

-

Solve someone’s problem.

-

Scratch someone’s itch.

-

Exploit someone’s weakness or misunderstanding.

The new age of transparency means the latter two are becoming more difficult, and the last one is becoming nearly impossible in some industries.

Part 2: Taking care of all stakeholders

Lehman Brothers’ stock peaked in 2007. It was bankrupt 10 months later.

It’s shocking how close these two events occurred. But when you piece together what happened, it starts to make sense. And it shows how dangerous it can be to be a business with a single goal of taking care of shareholders.

The death of one of the oldest and largest banks in the country isn’t caused by one thing, and it can’t be explained in simple points. But a big factor was its gradual shift from a focus on clients to a focus on profits.

Months before it went under, Lehman CEO Dick Fuld told shareholders on a conference call that “our goal is simple; that’s to create value for our shareholders.”

This was a common message.

Lehman’s 2006 annual report explained that the company had one goal: “maximizing shareholder value.”

As the banking industry began to break in 2008, Fuld put a peculiar amount of focus on the company’s short-term stock price. “I will hurt the shorts, and that is my goal,” he said in April 2008.

These comments might seem benign. But they’re not.

All business transactions sit on a spectrum, with customers on one end and shareholders on the other. Between those points are employees, suppliers, the community, regulators, and other stakeholders.

All businesses have to choose how much effort they put into looking after the well-being of each one of those stakeholders. Lehman put almost all its effort into one stakeholder — shareholders — with a goal of profits be damned at the expense of clients, financial markets, or the broader economy.

A company that doesn’t balance the needs of all stakeholders will eventually need to correct its imbalance, since no stakeholder can be abused indefinitely. And correcting those imbalances, as Lehman found, is often too much for a company to handle.

This is a tough balance to strike. The pendulum of power between stakeholders has swung from one extreme to the other over the last century.

In the 1920s, big shareholder returns came at the expense of poverty wages for millions of workers.

In the three decades after World War II, big wage gains and a thriving middle class gave unions so much power that corporate profits were smothered to the breaking point, which came in the early 1980s.

Over the last 30 years, we’ve swung back to a system where, on average, the sole mission of many businesses is profit maximization, even if it comes at the expense of other stakeholders. That’s pushed income inequality back to heights not seen since the 1920s.

As the world opens up and everyone becomes more aware of how everyone else is doing, there is a newfound push toward businesses that actively take care of every stakeholder in their organization. Employees need to be taken care of. Suppliers need to be taken care of. Customers. Communities. The environment. And, yes, shareholders too.

This trend isn’t just about businesses having empathy toward others — although that social mission is worthy enough. It is one of the clearest ways to reward shareholders in the long run.

Investors should only get excited about the prospect of something that not only works but works in harmony for everyone who is involved with it. That’s the only way you can be reasonably sure that something is sustainable indefinitely. And indefinite sustainability is where the largest compounding gains are found.

When your view of the world is restricted to the narrow lens of what you see around you, it’s easy to view business as a competition where the winner is whoever can drive others furthest into the ground. But when you zoom out and see how important cooperation of all parties is to making a business work in the long run, you realize how smart it is to lift others off the ground in an attempt to keep them happy and motivated. And as the world becomes more open and connected, more people’s views of the world zoom out. Which is why it’s an increasingly important business philosophy to go out of the way to take care of all stakeholders. It assists everyone, including shareholders.

Astro Teller, a former Google employee, put it another way: “Purpose is the point. Profit is the result. It’s the natural order of things.”

Part 3: Where the world is going

None of these ideas matter without evidence that the incoming generation of investors takes them seriously and will put their money behind them. And there’s plenty.

For most of history, allocating capital was viewed as binary. You had philanthropy on one side and the pursuit of profit on the other. One of the biggest trends of the last decade is the acknowledgement that there is something in between.

More investors are going out of their way to invest in for-profit companies that put thought into their social mission. These are not charities. But they also don’t see profit as the singular win-at-all-costs goal. If the Gates Foundation is at one end, and Philip Morris at the other, then Costco — a business that goes out of its way to take care of all stakeholders — is in between. And more investors are opting for the Costco-type investments than Philip Morris-type investments.

This is not a small trend. Assets managed with an ESG factor are rising by trillions of dollars. The New York Times explains:

The amount of assets managed using ESG factors has more than tripled to $8.1 trillion since 2010, according to a report issued in November by the US SIF Foundation, which tracks sustainable investing. The TIAA-CREF Social Choice Equity Fund has doubled in size to a current $2.3 billion in the last five years. Exchange-traded funds linked to MSCI ESG indexes have tripled to $3 billion in the last three years.

Most of these funds don’t directly exclude any specific industry. Instead, they rank companies against their peers based on how well they’ve performed on certain characteristics of taking care of all stakeholders. Rather than solely ranking stocks based on market cap, profits, or revenue growth, these funds also consider factors like employee compensation and environmental impact. The Times gives a good example:

In oil and gas, the Norwegian giant Statoil ranks near the top based partly on its record of spills and low emissions, while the American company Chevron ranks near the bottom with higher-risk operations, including forced shutdowns this year of a new $54 billion liquefied natural gas plant in Australia.

This is an important point. Extreme shifts away from norms can be socially more exciting, but realistically less feasible. They can shake up the existing order too much to be sustainable.

What’s promising about the shift toward ESG investing is that interest in it is huge, but the mechanics of the movement itself are not so dramatic that things like portfolio diversification are being upended. There is a push toward preferring investments in companies that care for all stakeholders. But it is not a black-and-white, pitchforks-and-torches surge. This calm, collected shift toward more thoughtful companies is precisely why the movement is so promising.

Some of the biggest investment shops are putting resources behind this trend. The Economist explains:

In the past two years BlackRock, the world’s biggest asset manager, launched a new division called “Impact”; Goldman Sachs, an investment bank, acquired an impact-investment firm, Imprint Capital; and two American private-equity firms, Bain Capital and TPG, launched impact funds. The main driver of all this activity is investor demand.

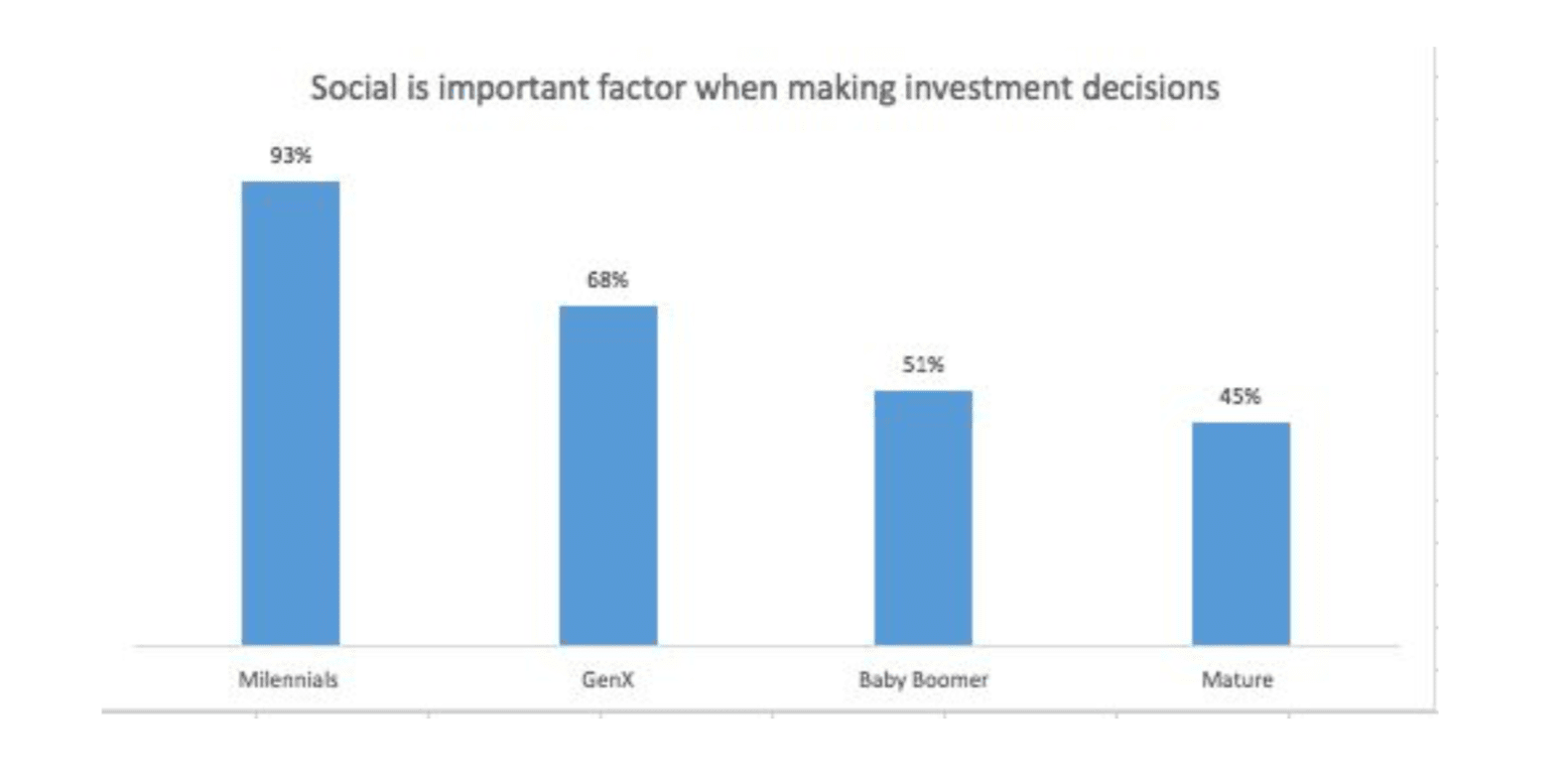

Interestingly, that demand is overwhelmingly from young investors. U.S. Trust surveyed 700 clients last year, gauging their interest in social-impact investments. When asked about the importance of social factors when making investment decisions, the results were clear:

Source U.S. Trust

It helps to go back and realize how previous young generations’ views shaped the world they eventually inherited.

The Greatest Generation saw a world that didn’t need to adhere to the ludicrously strict social and gender standards of their ancestors. They moved from a world in the early 1900s where, as historian Frederick Lewis Allen wrote, “At any season a woman was swathed in layer upon layer of underpinnings — chemise, drawers, corset, corset cover, and one or more petticoats,” to one where Rosie the Riveter helped win World War II in denim coveralls.

Baby boomers saw the racial segregation that their parents found normal to be abhorrent. They pushed for equal rights and have made tremendous progress over the last 40 years. They have also increasingly removed gender as a barrier to any profession.

These views seemed far-fetched at the beginning of each new generation. But they became reality because each generation eventually took control of capital, business, and politics.

When you claim the younger generation has marginally higher expectations of transparency, inclusion, and empathy, you’re not claiming they’re morally superior. You’re just pointing out the normal progression of events when a generation grows up with wider access to information, slightly better living standards, and a little more bandwidth to think about how other people go about their day.

Physicist Max Planck once explained why science was slow to change. New concepts, he said, aren’t accepted by changing people’s minds. Instead, science accepts a new truth “when its opponents eventually die, and a new generation grows up that is familiar with it.”

It’s the same with culture and social norms. A lot of these ideas — the Internet promoting product transparency, for example — are available and obvious to today’s older generation. They’ve learned to use them, and see the benefits. But for the younger generation, who has never known anything different, these aren’t new tools; they’re just a reality of how the world works and business gets done. New social norms can be hard to understand if you haven’t grown up with them. But for those who have never known anything different, there’s no other way.

Baby boomers ushered in similar improvement in their day. As did the Greatest Generation. And now millennials — on the cusp of taking social, economic, and political power — are in the early stages of nudging the economy, ever so slightly, in a new direction.