An Economy That Works for Everyone

We can build an economy that works for everyone, rather than a few.

In many ways, we already are. The trick to keeping it going is convincing people that no one needs to sacrifice to spread the benefits of economic growth more broadly.

To convince you, let me tell you a story about car tires.

The value of a comfortable business partner

It’s the early 1990s. Costco is negotiating with a tire distributor.

The two hashed out a deal. It wasn’t particularly lucrative for the tire distributor, but Costco was a growing retailer with loyal customers, and tire companies were itching to get involved.

A week after the deal was signed, Costco called the distributor. They needed to renegotiate.

“I can’t negotiate,” the tire distributor allegedly said. “I can’t go a penny lower on this deal without losing money.”

Yes, that was why they needed to renegotiate, Costco said.

After signing the deal, Costco realized it would be squeezing the tire distributor to the razor’s edge of unprofitability. It didn’t want a business partner in that position. So it tore up the original deal and raised the price it would pay for tires.

This was not altruism.

A business partner that can stick around for many years is worth more than one that will have to be replaced in a year or two. A business partner who is taken care of is more likely to take care of you. A business partner that does well will give you less day-to-day hassle than one that feels suffocated.

This is obvious — but only if you can forgo maximizing short-term profits to focus on long-term rewards.

That’s one of Costco’s enduring traits.

“We want to build a company that will still be here 50 and 60 years from now,” founder and former CEO Jim Sinegal has said. “I think the biggest single thing that causes difficulty in the business world is the short-term view.”

This ethos goes beyond business relationships. Costco pays employees an average of 72% more per hour than rival Sam’s Club. That is awesome for the employee, but it’s awesome for Costco, too. Its labor turnover is rock bottom: 17% per year for Costco versus 44% for Sam’s Club. In 30 years, Costco has never had a major employee strike or protest.

This has not come at the expense of shareholders: Costco stock is up more than sevenfold in the last 20 years, more than double that of the S&P 500.

We know this idea works. It can work for everyone — so long as you can convince them it’s true.

A historical perspective on equality

Before we discuss how to do that, a little history on how we got here.

The defining characteristic of economics in the 1950s is that the country got rich by making the poor less poor. Average wages doubled from 1940 to 1948, then doubled again by 1963.

Not long ago, the economy actually worked fairly well for most people. It didn’t last long, but for a short stretch after World War II through the late 1970s, economic growth was split fairly evenly between those who worked and those who invested.

The wealth inequality that defined the 1920s unraveled after the war as workers gained bargaining power and high profit margins became unacceptable during the war years. In 1955, Historian Frederick Lewis Allan wrote:

The enormous lead of the well-to-do in the economic race has been considerably reduced.

It is the industrial workers who as a group have done best — people such as a steelworker’s family who used to live on $2,500 and now are getting $4,500, or the highly skilled machine-tool operator’s family who used to have $3,000 and now can spend an annual $5,500 or more.

America’s Gini coefficient, a statistical measure of income inequality, fell by almost half from 1929 to 1970 as the distribution of income leveled out, shifting more of the nation’s income to lower-wage workers. The share of the nation’s wealth owned by the bottom 90% of families rose from 15% in 1929 to more than 35% by 1985.

It was the era of the high-wage middle class — the classic stories of single manufacturing workers supporting a family with a dignified life. The country thrived, and average workers took home the biggest prizes.

And the most amazing thing about this era is how little sacrifice was required from the investors who financed those workers’ businesses.

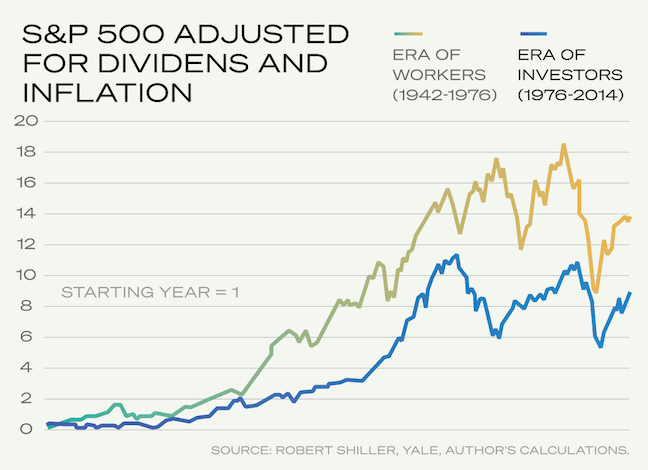

The average annual stock market return from 1880 to 2019 is 10.92%, according to a database maintained by Yale economist Robert Shiller.

From 1950 to 1975 — the era when the balance of economic power shifted from investors toward workers — the market returned 12.9% per year.

Nothing is ever perfect, and the “glorious” middle years of the 20th century are filled with racial strife and areas of abject poverty. But if there was ever an era when the economy seemed to work for almost everyone — when average workers and investors thrived simultaneously — it was the postwar boom years.

But nothing in economics stays the same forever.

In 1976, two economists wrote a paper with a boring name that would go on to influence the world in ways they likely never imagined. “Theory of the Firm: Managerial Behavior, Agency Costs and Ownership Structure,” argued that businesses would be run more efficiently if management acted like owners and aligned their incentives with shareholders. Pay managers with stock and focus on profit maximization, and companies will be better off.

It became the most cited economics paper of all time, an academic bible and intellectual foundation for business thinkers and policymakers. And it began a slow movement toward profit maximization as a business’s top priority, a goal that has defined most of the last 40 years.

Who does inequality actually benefit?

The statistics that define the modern era of wealth inequality need no introduction.

Most of us have heard the stats about how much the wealth of the top 1% has grown and how economic growth has shifted from worker wages to corporate profits.

The numbers have been repeated enough, and they’re usually presented in a way that frames them as exploitive, which brings out the tribal war instincts. Few topics are as divisive as wealth inequality and what to do about it.

What I’ve always found astounding is how little evidence there is that the era of rising corporate profits and shrinking worker wages was actually good for investors.

Source: Robert Shiller, Yale, author’s calculations.

These comparisons are never apples to apples; changes in valuations, interest rates, and countless other variables differ from era to era.

But it is an unavoidable irony that as soon as the economy shifted its priority from worker wages to maximizing shareholder profits, shareholder returns declined.

It’s nearly impossible to link cause and effect. You have to wonder, though, whether the entire economy went from operating like Costco to operating like Sam’s Club.

Thinking longer-term

When Facebook went public in 2012, Mark Zuckerberg wrote: “We don’t build services to make money; we make money to build better services … I think more and more people want to use services from companies that believe in something beyond simply maximizing profits.”

But, he explained, this was 100% aligned with taking care of shareholders:

By focusing on our mission and building great services, we believe we will create the most value for our shareholders and partners over the long term—and this in turn will enable us to keep attracting the best people and building more great services.

We don’t wake up in the morning with the primary goal of making money, but we understand that the best way to achieve our mission is to build a strong and valuable company.

The idea that taking care of customers and employees does not sacrifice returns but actually enhances them in the long run largely comes down to a difference in time horizon.

Cutting salaries and squeezing your product quality may boost profits in the short run. But long-term shareholder return comes from attracting the most loyal customers and the most talented employees. And that comes from taking care of everyone — an economy that works for everyone.

General Motors went from the most profitable company in the world in the 1960s to bankrupt in 2009. A lot happened between those years, including the rise of foreign competition. Former Vice Chairman Bob Lutz attributes the decline overwhelmingly to one trait: GM lost its way when the “car guys” were overrun by the “bean counters” and profits took precedence over products.

He wrote in his memoir:

Leaders who are predominately motivated by financial reward, who bake that reward into the business plan and then manipulate all other variables in order to “hit that number,” will usually not hit the number, or, if they do, then only once. But the enterprise that is focused on excellence and on providing superior value will see revenue materialize and grow, and will be rewarded with good profit.

Is profit an integral part of the business equation and a God-given right, no matter how compromised the product or service? Or is the financial result an unpredictable reward, bestowed upon the business by satisfied customers?

Most of these comments seem obvious. They’re hard to argue with. But they are, for the most part, the exception.

Squeezing employees as much as possible in favor of maximizing profits has been the default strategy for most of the last several decades, particularly for workers at the bottom end of the spectrum. The result, again, hasn’t been intuitive. By maximizing shareholder value, companies often do the opposite.

In 2013, The New York Times received leaked notes from an internal Walmart meeting. The paper wrote:

Walmart, the nation’s largest retailer and grocer, has cut so many employees that it no longer has enough workers to stock its shelves properly, according to some employees and industry analysts. Internal notes from a March meeting of top Walmart managers show the company grappling with low customer confidence in its produce and poor quality. “Lose Trust,” reads one note, “Don’t have items they are looking for—can’t find it.”

Who does this help? Not employees. Not customers. Probably not shareholders, either.

Everything about economics exists on a spectrum. Few things are wholly good or wholly bad. Most things can be good at one level, neutral at another, and backfire at another. Everyone wants businesses to run efficiently and to reward shareholders who take risks.

But it’s clear, on so many levels, that the push in the past 40 years toward profit maximization, which came at the expense of workers, went too far. Workers have suffered, and the shareholders don’t have much to show for it.

Over time, economies are good at balancing out distortions. Capitalism doesn’t like outliers. It pushes them back towards a happy medium. Trends grow, plateau, then reverse.

We’ve already seen that happen in the last few years.

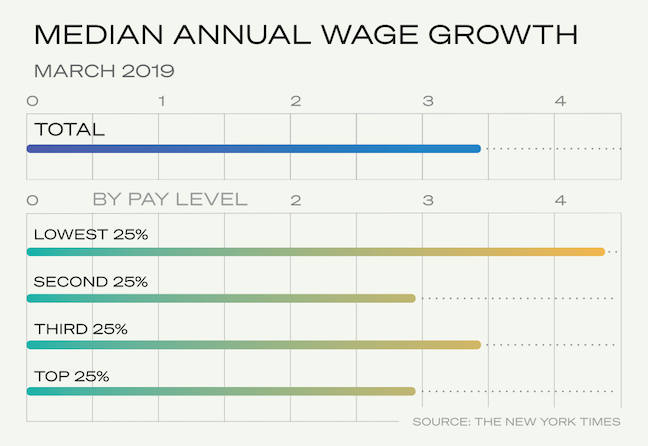

Wage growth over the last three years was actually highest for the lowest-earning workers. Median wage growth was the highest it had been in almost two decades.

Source: NYT.

This isn’t a fluke. There are concrete reasons why we should expect the trends of the last four decades to unwind — and why we should expect more building of an economy that works for everyone.

Caring for customers, employees, and shareholders

Every organization has three main stakeholders: customers, employees, and shareholders. John Mackey, co-founder of Whole Foods, once told me that every business takes care of at least one of them. Some care for two. Few care for all three. The easiest way to make a business work is to exploit at least one stakeholder.

That’s how it’s traditionally worked, at least. But it’s getting harder.

The greatest innovation of the last generation has been the destruction of information barriers that used to keep strangers isolated from one another. What’s happened over the last 20 years — and especially the last 10 — has no historical precedent. The telephone eliminated the information gap between you and a distant relative. But the internet has closed the gap between you and literally every stranger in the world. It fundamentally changes how the economy works because it makes it harder for companies to hide how they treat stakeholders.

Think of how much open access to information has been a defining characteristic of the millennial generation. No one’s life has been hidden, because we grew up with Facebook. No one’s career is a mystery, because we grew up with LinkedIn. Few purchases are a gamble, because we grew up with Amazon reviews.

In the same way that baby boomers had marginally less tolerance for gender discrimination than their parents, millennials have marginally less tolerance for hidden information.

The explosion of online content has two sides. Everyone has a platform to tell their story and share their information. And everyone is also watching one another, waiting for someone to slip up so they can reveal the underlying inefficiencies and bad behavior.

Yelp and Glassdoor can now accomplish in an instant what investigative journalists spent whole careers doing just a decade ago.

Twitter gives a global microphone to people who were silenced just a few years ago.

Valeant Pharmaceuticals, now Bausch Health, collapsed amid accounting issues four years ago. The guy who exposed it wasn’t from a big Wall Street bank or newspaper. He’s a sleuth who works from home and publishes his work online for everyone to see.

Companies that take care of all their stakeholders will have an economic advantage over those who don’t because they’ll be able to attract and maintain the best employees and most loyal customers.

By not making profit maximization the first priority, you will, in effect, increase your chances of maximizing profits.

That’s it. That’s how we create an economy that works for everyone: by making them realize that no one has to sacrifice to make it so.